An eminent Lithuanian rabbi is irritated that his yeshiva students dedicate their breaks to playing soccer rather than learning about the Torah. Intended to persuade their rav of the beauty of the game, the students invite him to see a professional match. We ask at half-time what he feels.

“I’ve solved the problem,” says the rabbi.

“How?”

“Give one ball to each side, and they will have nothing to fight over.”

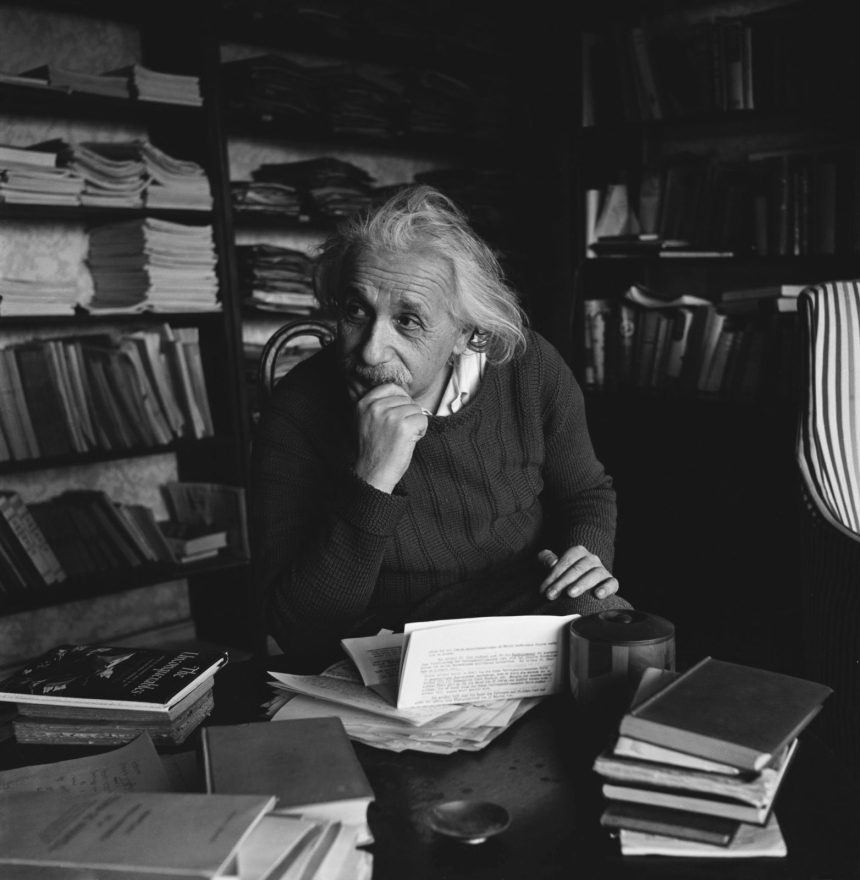

I have this (apocryphal) anecdote from the new book of Norman Lebrecht, “Genius & Anxiety,” an erudite and delightful study of Jewish philosophers, artists and entrepreneurs ‘ intellectual successes and anxious lives between 1847 and 1947. Sarah Bernhardt and Franz Kafka; Albert Einstein and Rosalind Franklin; Benjamin Disraeli and (sigh) Karl Marx— how could a nation that never exceeded one-third of the world’s population contribute so seminally to so many of its most path-breaking thoughts and innovations?

The common answer is that Jews are intelligent, or appear to be intelligent. As far as Ashkenazi Jews are concerned, it is real. “The Jews of Ashkenazi have the highest average I.Q. Of any ethnic group for which accurate data are available, “noted one paper from 2005. “They made up only 3% of the U.S. population in the 20th century, but earned 27% of the U.S. Nobel prizes for research and 25% of ACM Turing prizes. More than half the world chess champions are portrayed by them.

Also Read: Israeli student subjected to foul-mouthed anti-Semitic tirade on New York subway

But the explanation of “Jews are smart” is more obscure than it illuminates. Apart from the recurrent nature-or-nurture problem of why so many Ashkenazi Jews have higher I.Q.s, the more difficult question is why such bracing originality and high-minded intent so often accompanied that intellect. In the service of prosaic stuff, one can apply a prodigious intellect — formulating a war plan, for example, or constructing a ship. One can also use creativity to represent an error or a crime, such as running a planned economy or stealing a bank.

Yet Jewish intelligence operates differently, as the Lithuanian rabbi’s story suggests. It is inclined to challenge the idea and reconsider the concept; to wonder as often as possible why (or why not?); to see the absurd in the mundane and the sublime in the ridiculous. Ashkenazi Jews may have a marginal advantage in thinking better than their gentile peers. Where their advantage is to think differently more frequently.

Where do these habits of mind come from?

There is a religious tradition that asks the faithful not only to observe and follow, but also to debate and disagree, unlike some others. Jews are never-quite-comfortable in places where they are the minority— intimately familiar with the country’s customs while keeping a critical distance from them. There is a religious principle, “incarnate in the Jewish people,” according to Einstein, that “the individual’s life has meaning only[ insofar] as it helps to make any living thing’s life more noble and beautiful.”

And there’s the belief, born of prolonged exile, that all that looks solid then meaningful is actually perishable, while all that’s intangible — most of all knowledge — is potentially immortal.

“We were well off, but that was all we got out of,” remembered the late financier Felix Rohatyn of his narrow escape from the Nazis as a child in World War II, with a few secret gold coins. “Since then, I have had the impression that what you bring around in your head is the only lasting property.” If the greatest Jewish minds seem to have no walls, it may be because, for Jews, the walls have so often come down.

Also Read: Trump delivers remarks at the Israeli American Council National Summit

These explanations for Jewish brilliance aren’t necessarily definitive. Nor are they exclusive to the Jews.

The American university can still be at its finest a place of constant intellectual challenge instead of political conformity and social group thought. The U.S. can still be at its finest the nation that values, and sometimes rewards, all sorts of heresies that offend polite society and contradict existing belief. At its strongest, the West should uphold the concept of cultural, social, and ethnic pluralism as an endorsement of its own diverse heritage, not as a grudging accommodation for outsiders. That makes Jews different in that sense is that they are not. They’re generic.

But the West is not at its best. It’s no wonder, though under different guises, that Jewish hate has made a comeback. Anti-Zionism took the place of anti-Semitism as an anti-Jewish political program. As secret agents of economic iniquity, globalists have taken the place of rootless cosmopolitans. White nationalists and black “Hebrews” murdered Jews. Hate crimes targeting orthodox Jews in New York City have become an almost daily reality.

The hatreds would have known Jews of the late 19th century. Early 21st century Jews should know where they might lead. What is no mystery about the Jewish creativity is that it is a frightfully fragile flower.