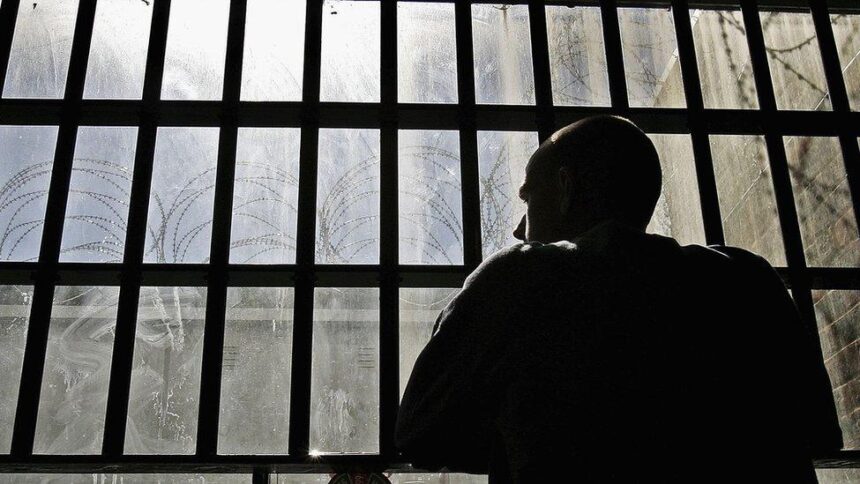

A joint review by the chief inspector of prisons and the chief of Ofsted reveals that youngsters are detained in cells to avoid conflict.

According to a report, there are too many children kept in youth offender institutions (YOIs) cells as staff struggle to keep warring youngsters apart and are being denied access to education.

The reports document an alarming fall in the quality and quantity of education offered to youngsters from 15 to 18 years old in YOIs over the past decades, even though the number of teenagers in custody has declined significantly.

In some extreme instances, youngsters are locked up in their cells for up to 23 and a half hours a day because of the weakening ability of teachers and YOIs staff to handle challenging and sometimes violent behaviour.

According to the joint review of YOI education by the chief inspector of prisons, Charlie Taylor, and the head of Ofsted, Sir Martyn Oliver, children in YOIs receive far less than 15 hours of education a week in reality. In comparison, they are meant to receive 15 hours of education, less than half of what their colleagues receive in school. Lessons are frequently called off because there is no YOI staff to escort the teenager to the classroom or no teacher to teach the youngster.

The report concludes that over 400 teenagers in custody are “receiving a poor education that fails to meet their needs” because of poor-quality resources, a severe shortage of staff and a lack of training and qualification among staff.

Teenagers are also often kept in classes that have little to do with educational needs or interests but are determined by a “labyrinthine” system of “keep parts” or “non-associations” created to keep teenagers who are in conflict away from each other.

According to the report, inspectors discovered 388 “keep apart” arrangements in a population of just 89 teenagers in one YOI, making moving into the building challenging and nearly impossible.

Too often, teenagers are engaged in colouring or word search puzzles instead of learning skills that might benefit them after they are set free.

The report was compiled based on a joint review of 37 joint of the four YOIs in England by the chief of Ofsted and the prisons inspectorate. One of the Joint was shut down over a decade from 2014 to 2024.

Oliver stated, “I am deeply concerned by these findings. The children in these institutions are entitled to a high-quality education that supports them in turning their lives around. The system is failing them.”

Taylor said many children in custody haven’t been in school for years because they have truanted or been excluded while describing the report as “depressing”.

He stated, “Their time in custody should be a golden opportunity to begin filling in some of these educational gaps—assess what they need to learn and provide high-quality teaching so that, when they leave, they are in a better position to avoid a return to custody.

“Too often, our colleagues in Ofsted find that attendance is very low, behaviour is not good enough, the curriculum is not suitable and the quality of teaching is poor.”

The Prisoners’ Education Trust chief executive, Jon Collins, stated that the report’s findings were shocking but unsurprising. “More of the same is simply unacceptable if we want to give these young people the skills and qualifications they need to have a chance in life.”

Nic Dakin, the minister of justice, stated: “This government has inherited a criminal justice system in crisis, and these damning reports highlight the unacceptable strain that has been placed on the youth estate for too many years. We are determined to tackle these challenges head on – giving staff the support they need to reduce violence, increase access to education and help these children turn their lives around.”